Strong Financial Underpinning A Key Requisite to Strong Crop Insurance Policy

Because of the magnitude of risk inherent in U.S. agriculture, combined with the large volume of commodities produced, companies that participate in the Federal crop insurance program are mandated by law to have ready access to large pools of liquid capital so they can meet their obligations if disaster strikes the farming sector. These rigorous financial requisites all but demand the involvement of reinsurers – large, financially fortified companies that provide insurance to insurance companies – to ensure that payments arrive to farmers for the policies they purchase in a timely fashion.

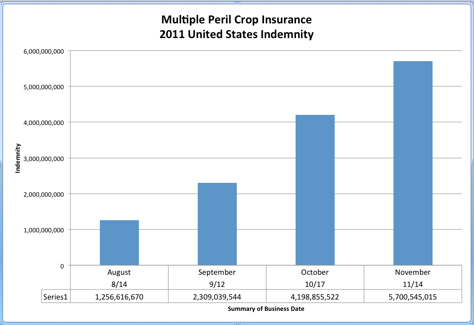

Never before in the history of the Federal Crop Insurance Program was the extent of the risk and financial exposure so evident as in 2011, which saw record indemnities in excess of $10.4 billion paid by private companies to farmers for their losses. This makes 2011 the most expensive year ever, topping the old record set in 2008 of $8.67 billion in indemnities by 20 percent. And with commodity prices rising due to tight markets and increased domestic and global demand, there will likely be an increased need for crop insurance, which protected over $113 billion worth of crops in 2011.

Although crop insurance has already been subjected to $12 billion in federal funding reductions, further reductions could raise questions of the federal commitment to the existence of a robust and effective crop insurance policy. “An unrecognized danger is that additional budget cuts will prove counterproductive in the long run, driving away the reinsurance companies that have long played a crucial role in the program’s growth by putting a substantial amount of their capital at risk,” says Jim Christianson, Managing Director, Guy Carpenter & Company, LLC.

Christianson notes that any pullback by reinsurers would have serious repercussions in the market and would, in the end, leave the federal government and the U.S. taxpayer to shoulder a greater portion of the cost of future catastrophes that hit the country’s agriculture sector.

As recently as the early 1990s, farmers purchasing crop insurance hovered around 30 percent. But the program has expanded dramatically since and in 2011, more than 1.1 million policies were written, covering 83 percent of eligible farmland and 128 crops in all 50 states. And the continued climb in commodity prices means an increase in the amount of risk that will be protected annually.

“Today, reinsurers from around the world find the U.S. crop insurance market to be a welcome addition to their portfolios,” said Christianson.

Reinsurers are keeping a watchful eye on Congress and lawmakers as they write the 2012 Farm Bill. ”Congress should be very cautious about considering the adoption of any other policies that would weaken the already over-extended crop insurance infrastructure or divert the much needed reinsurance investments elsewhere,” he added.