‘Don’t Mess with Crop Insurance’

“Don’t mess with crop insurance.”

The phrase has become a battle cry among farmers in the Midwest, especially as legislators headed out for listening sessions and town halls ahead of the next farm bill.

And so far, legislators are hearing the message.

That’s the opening of a recent Farm Futures article about crop insurance.

The piece points out that crop insurance has become the most popular safety net for farmers because it replaces the costly emergency disaster relief bills of the past. Back then, when a storm destroyed crops, farmers had to ask Congress for help. The system was expensive for taxpayers and inefficient for farmers because of slow government payments.

Today’s modern crop insurance – where farmers design their own policies, pay premiums, shoulder deductibles and only receive indemnities after losses are verified by trained adjusters – is easier to manage and more accountable. And, since farmers are paying into it, taxpayers aren’t left shouldering all of the cost when disaster strikes.

It’s no wonder, as the article notes, that 83 percent of farmers in a recent survey said crop insurance was a very important part of their risk management plans.

Unfortunately, 75 percent also said they were worried that the next farm bill won’t provide an adequate safety net, showing the angst in farm country over low commodity prices and increasing weather unpredictability.

Amazingly, some lawmakers are looking to weaken crop insurance and leave farmers even more vulnerable. Art Barnaby of Kansas State University detailed why that would be such a mistake in a follow-up Farm Futures article.

Among the consequences, he found, of making crop insurance less affordable and less available:

- Most farmers, including relatively small grain growers, would be affected if the Harvest Price Option were eliminated – a popular product similar to “replacement value” in other lines of insurance.

- Proposed caps on premium assistance would be hit by numerous farms across the country, including specialty crop farms as small as 200 acres in some California counties.

- Forcing farmers to pay more for insurance could affect coverage levels and weaken the system – an idea backed up by the Farm Futures survey, which found that 84 percent of farmers said they couldn’t afford adequate coverage without federal assistance.

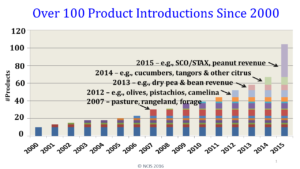

Farm Futures also looked back at crop insurance data since the late ‘80s and found a system that is in balance and is providing high levels of protection.

“Since 1988, crop insurance policies have covered $15 trillion to guard against losses,” the publication noted. “During the same period, total premiums paid were $136 billion and total indemnities paid to farmers came to $116 billion.”

In other words, crop insurance is working as designed and the consequences of weakening it could be dire.

“Don’t mess with crop insurance.”

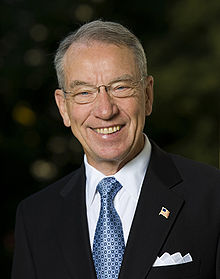

Iowa Republican Senator Chuck Grassley says his top Farm Bill priority in the 115th Congress is to preserve a vigorous crop insurance program, noting there is no safety net more valuable to farmers and taxpayers.

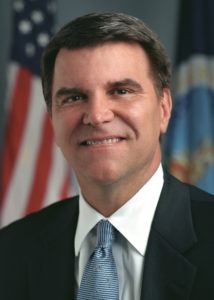

Iowa Republican Senator Chuck Grassley says his top Farm Bill priority in the 115th Congress is to preserve a vigorous crop insurance program, noting there is no safety net more valuable to farmers and taxpayers. Prior to the holidays, National Council of Farmer Cooperatives President and CEO Chuck Conner found himself in a strange place – onstage at a

Prior to the holidays, National Council of Farmer Cooperatives President and CEO Chuck Conner found himself in a strange place – onstage at a  Grassley recently surveyed the flood damage in several eastern Iowa cities, and discussed his experience on

Grassley recently surveyed the flood damage in several eastern Iowa cities, and discussed his experience on