Drought Worsens As USDA Cuts Crop Projections; Farmers Hopes Sink

The weekly U.S. Drought Monitor map released August 14 held more bad news for the contiguous United States, with 62 percent remaining in some level of drought. And the expanse that is gripped by extreme or exceptional drought rose nearly two percent last week to 24 percent.

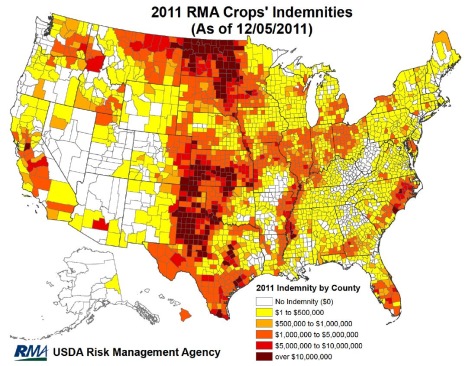

The center of the drought remains directly over the Corn Belt. With some stage of drought covering the entire states of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri and Kansas, the drought is certainly taking its toll on the corn and soybean crops. According to the August 10 estimates from USDA – the first “in the field” estimates of the year – production numbers are down substantially from what was projected at the beginning of the planting season.

Despite the fact that this was the largest corn crop planted since 1937, production is projected to be down 13 percent, the lowest output since 2006. Corn yields are expected to average 123.4 bushels per acre, down nearly 24 bushels from last year, which would be the lowest average yield since 1995. Soybeans tell a similar story. Soybean production is forecast to be down by 12 percent from last year, and if realized, would have the lowest average yield since 2003.

“Thankfully, the vast majority of the farms in these drought-ravaged areas are protected by crop insurance,” said Tom Zacharias, president of National Crop Insurance Services, in a statement released to the media. Zacharias noted that farmers purchase crop insurance policies to protect themselves against situations just like this, although many have never collected an indemnity. “This year, their decision to purchase crop insurance confirms their practice of sound risk management,” he said.

While there continues to be speculation about the ultimate cost of the 2012 drought, it is still too early to provide precise estimates of the losses. Zacharias explained that NCIS is analyzing the August 10 report and will compare that with reports from the field along with the crop insurance policy data that is still being processed and reported to the Risk Management Agency.

It will be hard to gain a complete picture of the situation and final outcomes will vary by state, crop and types of policies purchased. “What is certain is that the crop insurance industry is on the ground in the drought-stricken areas, mobilizing loss-adjuster teams,” Zacharias pointed out.

“Farmers can be assured their claims will be paid, and that the companies will move as quickly and as efficiently as possible, given the expected volume of claims, to assess damages and get indemnity checks into the hands of farmers.”

In order to be approved to sell federal crop insurance, companies must have adequate surplus and reinsurance at their disposal so that even if a catastrophe of this magnitude strikes, and then one strikes again the next year, the company is still capable of paying indemnities on the policies they sell.

In addition to company surplus and reinsurance, the federal government serves as the backstop reinsurer for all companies that sell crop insurance. As such, the federal government shares in the gains and the losses of the program. Gains in prior years can and will be used to offset losses in years like this one.

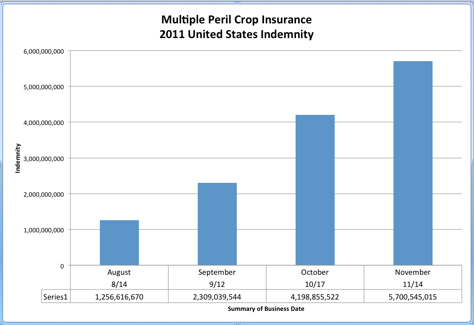

Zacharias explained that the industry has 5,000 claims adjusters and 15,000 agents working tirelessly right now to help growers cope. These adjusters are working hard to get money to farmers who have suffered losses, already paying out more than $1 billion in indemnities to date. Companies are also mobilizing adjusters away from other parts of the country that have not been affected by drought and sending those adjusters to the hard-hit states.

“With their crop insurance policies in hand, farmers will not only survive this drought but plant again next year, ensuring a continuity of the food, feed, fiber and fuel supply for this nation and an increasingly hungry world,” he added.